This is the first in a series of three stories about the lower section of the Lumber River and the revitalization of Fair Bluff. A future series will feature the upper Lumber River.

On any given weekend in the southern mountains of Virginia, hundreds – sometimes thousands – of cyclists pedal the 17 miles from near the peak of Mount Rogers to Damascus, Va. It’s almost all downhill as the 1,700-foot descent winds along an abandoned paved or hardened rail bed that’s transected by wooden bridges spanning Laurel Creek.

A second stretch runs from Damascus on mostly flat ground to Abington, Va., completing the 35-mile trail.

Damascus, once barely clinging to life after the closure of its main industry in 1986, now thrives as cyclists and hikers crowd restaurants and stores almost year-round.

Two hundred and eighty-nine miles to the southeast lies Fair Bluff in Columbus County. Ravaged by floodwaters from the Lumber River following hurricanes Matthew and Florence, downtown is devoid of the throngs of people who once filled the streets during tobacco market. The crumbling historic brick buildings sit empty. The town clock on Main Street no longer tells the time, stuck on 11:30.

It is a tale of two towns, one of opportunity fulfilled, the other still looking for a new identity.

Thirty-four years ago, people in and around Abington and Damascus and a U.S. congressman representing the district had a vision for a transformational project that would capitalize on the growing number of cyclists and ecotourists coming from the cities looking for adventure. The railroad abandoned the line in 1977. Congress later appropriated $2 million to turn the railbed into a greenway. The result was the Virginia Creeper Trail, which opened in 1989 and is now visited by approximately 250,000 people annually.

Fair Bluff finds itself at a crossroads similar to that faced by Damascus in the mid 80s, which begs the question: Can the river that devastated the town twice in three years transform itself into a destination that will draw paddlers and other ecotourists from far and wide?

•••

Though it’s unlikely that hundreds of paddlers would take to the river on any given day, the pieces are in place to make Fair Bluff an ecotourism destination.

Lumber River State Park Superintendent Lane Garner believes the river and state park will grow as more people seek solace in the great outdoors.

Lane Garner, superintendent of Lumber River State Park. Photo by Les High

“We like to say we are in the forever business,” Garner says, “meaning we manage properties that will be protected forever. I hope to see more property protected through various agencies and conservation groups like the Lumber River Conservancy or private citizens that realize the importance of being good stewards to the environment.

“I also hope to see more recreation opportunities offered at the park with additional trails, both hiking and equestrian, camping opportunities like primitive and paddle-to sites, and RV sites. Recent floods have changed some of our plans because a majority of our land is in the floodplain, but with careful planning I hope to see additional facilities that can withstand future storms.”

Garner believes that as use of the river increases, the state park and Fair Bluff have the opportunity to grow with it. He envisions everything from private outfitters to a brewery and bed and breakfasts in Fair Bluff.

River Bend Outfitters

Richard Willis and the late Stacy King once ran an outfitting service on the river, operating for nine years from a small building at the boat landing in Fair Bluff.

King had a vision to promote Fair Bluff and its natural resources, Willis said. One result of that vision was River Bend Outfitters, founded in 1997. King, in his 70s at the time, owned canoes, kayaks, and other equipment, had an amiable demeanor, and “sought the best in people,” Willis said.

Willis, the younger of the two and in his 30s, did most of the guiding and heavy lifting of canoes and kayaks. He was working at a job out of state and looking for a way to get back to his hometown.

A group in front of River Bend Outfitters, which operated for nine years out of Fair Bluff by Stacy King and Richard Willis. Submitted photo by Richard Willis

Guiding people on the river was a natural fit for Willis.

“I loved the camaraderie and teaching people about the river and nature and all it has to offer,” he says.

River Bend had about 20 canoes and 20 kayaks. Most excursions were in the summer months.

“Some days we didn’t have enough canoes and kayaks and some days there would be a drought,” Willis says.

River Bend didn’t do many overnight trips because the Lumber River has little in the way of land adjacent to the water. Trips were mostly about four to six hours long, paddling from U.S. 74 to Fair Bluff, or three hours long, winding from Princess Ann to Fair Bluff.

Like everyone else who talks about the river, Willis notes that it can be dangerous, with varying degrees of water levels and velocity, snags or “strainers,” and sand bars. He generally required a guide for every seven boats.

There were the occasional incidents, including one couple who got into trouble and walked back to Fair Bluff after finding their way out of the swamp.

Willis believes another outfitter could make a go of it today. He says anyone getting into outfitting would probably need a supplemental income.

“It was mostly a weekend thing,” Willis says. “We had a lot of repeat customers. Now with all this traffic coming through town, who knows?”

An early group in River Bend Outfitter canoes near the take-out point in Fair Bluff. Submitted photo by Richard Willis

The river has its pluses and minuses for outfitting. Its narrow width and sharp turns make it hazardous for canoes and kayaks to share the river with motor boats. There aren’t a lot of take-out spots for lunches unless the water is low and sandbars are exposed. He loathes the increased logging of old-growth trees that are felled to within only 50 feet of the river, leaving ugly scars that will last a generation.

“But,” Willis says, “guiding on the river brought a lot of joy and pleasure to me personally. It’s such a tranquil place.

“If we can keep it in pristine condition…,” he says, his voice trailing off. “People don’t realize just how precious the river is.”

Reimagining Fair Bluff

Town Manager Al Leonard has been instrumental in trying to rebuild Fair Bluff after the hurricanes.

“Every community has to find out what its niche is,” Leonard says. “Fair Bluff’s is the Lumber River. With the growth in Myrtle Beach and Brunswick County, we want to align ourselves with what’s coming.”

Riverside Drive, Leonard notes, is full of pickup trucks during the warm months without much marketing or promotion. “It’s a really good place to spend a Saturday or Sunday with friends or family.”

The Columbus County commissioners, including Commissioner Randy Britt of Fair Bluff, funded a short section of the Fair Bluff River Walk, a winding, elevated wooden walkway that is adjacent to the Lumber River. It could easily be southeast North Carolina’s most beautiful trail.

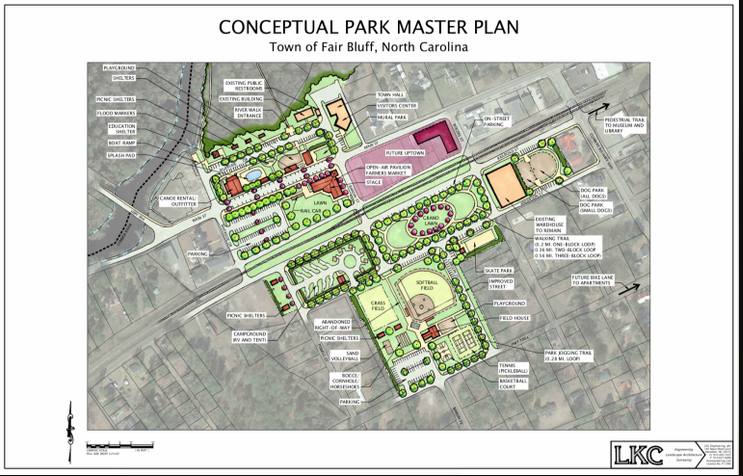

A proposed master plan for the new Fair Bluff park where downtown is currently sited.

Town Commissioner Willard Small and Leonard were members of the state’s Tobacco Trust Fund board and later secured a $450,000 grant to extend the boardwalk to three-quarters of a mile.

After repairing water and sewer infrastructure and moving the town hall and fire department to new facilities, Leonard and town commissioners began to work on Phase II of the recovery — aligning the economic future of Fair Bluff with the river.

A photograph taken after Hurricane Matthew shows a fiberglass ski boat navigating down Main Street with ease. The dirty water didn’t recede for days. Mold and mildew spread like wildfire inside businesses. The water eroded the old brick, rendering many buildings structurally unsound.

The future of the nearly bankrupt river town was, as Leonard once put it, “bleak.” Many residents left, shrinking the population from more than 900 to about 625.

But Fair Bluff has found a spark.

Trail Life Troop 1533 boys and leaders launch a canoe at Princess Ann landing. Photo by Les High

The River Walk remains. The town recently cut the ribbon on a new housing complex and received funding to build a new business district outside the flood zone.

Fair Bluff hopes to secure an N.C. Parks and Recreation Trust Fund matching grant that will create a park with campsites, a farmer’s market, open spaces with a pavilion, and recreational fields and courts, among other features where downtown now sits.

The trick, Leonard says, will be finding money to tear down the existing buildings to make way for a new Fair Bluff that would come to rely on the very waters that nearly destroyed it.

Small supports the plan to convert downtown Fair Bluff into a destination for people looking for the same sense of nature he’s enjoyed for his 96 years.

“The people here are friendly and the river is just beautiful,” he says. “I believe Fair Bluff will come back even better than before.”

An old school bus probably served as a fishing cabin back in the day. Photo by Les High

Economic development tool

Development can conflict with the environment, but the economic development directors in Columbus and Robeson counties, Gary Lanier and Channing Jones respectively, believe the river can spur green economic growth and jobs.

“The potential for ecotourism with the Lumber River is immeasurable,” Lanier said, noting that the Lumber has been designated one of North Carolina’s five “Wild and Scenic Rivers.”

“As an avid kayaker myself, I have spent many enjoyable hours on the Lumber River. There is a constant current in the river that allows you to sit back in your boat and just admire the wildlife while you drift down the river.”

Having more outfitters would be a benefit to ecotourism growth, Lanier says.

“For the less athletic among us, a touring pontoon boat would let a lot of tourists enjoy the river, especially those who may not be able to canoe or kayak. I would love to see anything that will enable more people to see what a wonderful natural asset we have.”

Lanier would like to see funding for a river tourism master plan in conjunction with the state park.

Jones said efforts to clear the river of debris have greatly increased the possibility of the Lumber River becoming a paddling destination.

“The ecotourism sector is something that really needs to be evaluated and looked at as a prospect,” Jones says. “It has the possibility of increasing dramatically because of the resources and funding that have come to the county to clean out the river. The accessibility of individuals who want to take scenic tours has tremendously changed. They have the ability to go in there and navigate the river in a way that hasn’t been done in years.”

‘Very high water quality,’ but for how long?

Though stained dark brown with tannins like most coastal rivers, the Lumber is remarkably clean, says Joseph White, a biology professor at the University of North Carolina-Pembroke.

White grew up near the Catawba River in the foothills of North Carolina.

“The Catawba and its tributaries are just as charming and beautiful as the Lumber, but very different,” White says. “Many of the Catawba’s tributaries start as rocky, fast-moving mountain streams surrounded by rhododendron and mountain laurel. The larger streams and rivers they merge to create are often disturbed by channelization, impoundments, development in the riparian zone, pollution, and the like.

High water covers the dock at the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission landing in Fair Bluff. Even though the water is dark with tannins, the Lumber River is remarkably clean. Water quality will be a key for ecotourism in the future. Photo by Les High

“It’s pretty special to have a major river like the Lumber that, at least to the naked eye, is in pristine condition. The fact that there are no dams, limited development on the river, and that water quality remains high, even with all of the activity going on in the watershed and the recent storms, really speaks to the gem the Lumber really is. Then add to that the bald cypress and Spanish moss, the swamps and wetlands…it really is a captivating place.”

White cautions that local and state governments must be diligent about protecting the river and the areas that surround it.

“Counties and municipalities can benefit from developing parks and features like the Fair Bluff River Walk and incentivizing new businesses that will foster and benefit from ecotourism,” White says. “However, I would urge counties to limit disturbance in the river’s floodplain or adjacent terraces, and that these developments have as small a footprint as possible. Fragmentation of the forests along the river will reduce the benefits of preserving the river.”

The greatest threats to the Lumber are pollution and the degradation of its high water quality, White says.

“Being in a rural area that is heavily farmed and with significant livestock operations, pollution should be a significant concern. This is pollution that washes into the river from fields, yards, and parking lots during rain events. It also includes things like fertilizers and pesticides as well as oil and grease, sediment from erosion on the uplands, and bacteria from pet or livestock wastes. The higher the abundance and concentration of these pollutants…the more concerning this threat becomes.”

The partnership with the conservancy permits UNCP students and faculty the use of protected properties for academic and research purposes.

“I think about how much the residents of the area and those who grew up here love and care about the river,” White adds. “I have the privilege of working with a few Lumbee folks, and to hear about the importance of the river in their history and culture is really moving.”